In theory, they can eat what they want, sleep as much as they choose and set aside their fears. In practice, some have had to be convinced there’s no longer a need to save a cherished bit of food in case there is none later.

At last, the 86 Israelis released during a short-lived truce between their government and Hamas are home. But the October 7 attack by Palestinian militants on roughly 20 towns and villages left many of the children among them without permanent homes to go back to. Some of their parents are dead and others are still held hostage, foreshadowing the difficulty of days ahead.

And so, step by step, these children, the mothers and grandmothers who were held alongside them, and their families are testing the ground for a path to recovery. No one, including the physicians and psychologists who have been treating them, is sure how to get there or how long it might take.

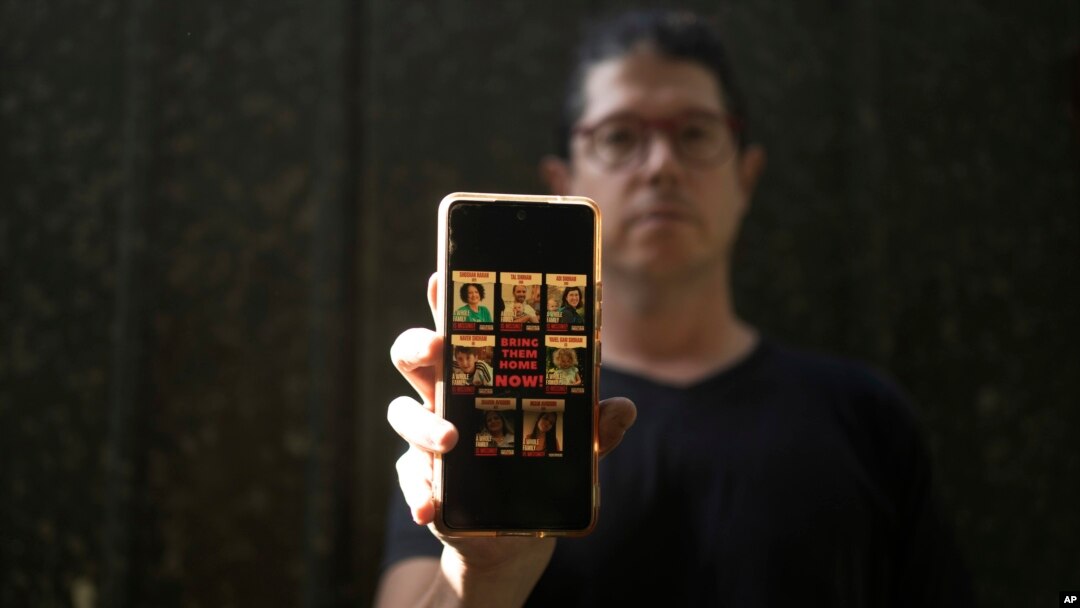

“It’s not easy in any way. I mean, they’re back. They’re free. But you can definitely see what they went through,” said Yuval Haran, whose family is celebrating the reunion with his two nieces, their mother and grandmother, while yearning for the return of the girls’ father, who remains a captive.

FILE - Yuval Haran, whose family is celebrating the return of his mother, his sister, and four others from Hamas captivity in the Gaza Strip, poses for a portrait with a picture on his phone of his family's hostage posters,in Herziliya, Israel, Decenber. 4, 2023.

“We’re trying to give them love, to give them hugs, to give them control back of their life,” said Haran, visibly exhausted by the stress of the past two months, but every bit as busy now as he rushes to fix bicycles and set up bank accounts for those who have returned. “I think that’s the most important thing, to give them the sense that they can decide now.”

It was clear as soon as the youngest were helped from helicopters that captivity had been brutal.

“They looked like shadows of children,” said Dr. Efrat Bron-Harlev of Schneider Children’s Medical Center in suburban Tel Aviv, who helped treat more than two dozen former captives, most of them youngsters.

Some had not been allowed to bathe during the entirety of their captivity. Many had lost up to 15 percent of their total weight, but were reluctant to eat the food they were served.

Asked why, the answer came in whispers: “’Because we have to keep it for later.’”

One 13-year-old girl recounted how she’d spent the entirety of captivity believing that her family had abandoned her, a message reinforced by her kidnappers, Bron-Harlev said.

“They told me that nobody cares for you anymore. Nobody’s looking for you. Nobody wants you back. You can hear the bombs all around. All they want to do is kill you and us together,” the girl told her doctors.

After enduring such an experience, “I don’t think it’s something that will leave you,” said Dr. Yael Mozer-Glassberg, who treated 19 of the children released. “It’s part of your life story from now on.”